December 12, 2016

Network for College Success

This year, the Network for College Success (NCS) advised a Chicago public high school to do something it had never tried before: It had all its teachers observe one another’s classrooms. “A lot of them had never been in another teacher’s classroom in their school—or in their entire career,” said Mary Ann Pitcher, Co-Director.

To their surprise, one group of instructors found that a student who’d had behavioral problems in their classes was actually leading discussions in another teacher’s room. They saw how the instructor eschewed the convention of having students only address the teacher; instead, the students interacted directly with each other. “Student-to-student dialogue is a research-based, effective practice that gets kids engaged in their own learning versus just sitting and acting in a passive, rote manner,” said Ms. Pitcher.

For the past decade, NCS has been breaking down the walls that too often separate educators. “A lot of what we do is combating professional isolation,” said Sarah Duncan, Co-Director. The organization does that by taking cuttingedge studies from the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research and helping high school principals and other leaders within Chicago Public Schools (CPS) turn that research into practice.

For NCS, the research always serves one overarching goal: preparing Chicago’s public high school students so that they can get into college and succeed there. “We want to ensure that every student in Chicago schools receives the education they deserve,” said Ms. Duncan. Eighty-five percent of CPS students are African-American or Latino and 85 percent of them are from low-income families.

NCS partners with 17 high schools that educate 19,000 students—20 percent of the entire CPS high school population. On a monthly basis, NCS brings together school leaders principals, assistant principals, counselors, and data specialists—to examine their schools’ data, such as grades and attendance. The school leaders learn about Consortium research that could help improve those markers of student success.

The research-to-practice translation takes ongoing external support—precisely what NCS provides. It sends its 16 coaches, who are former principals, counselors, or teachers themselves, into the high schools to serve as a thought partner and an expert outside eye.

“As a principal, you are doing, doing, doing under so much pressure that it’s very difficult to stop and think more broadly about working strategically with your school leaders and teachers,” said Amy Torres, Leadership Coach. “Without a community like the Network for College Success, it’s virtually impossible.”

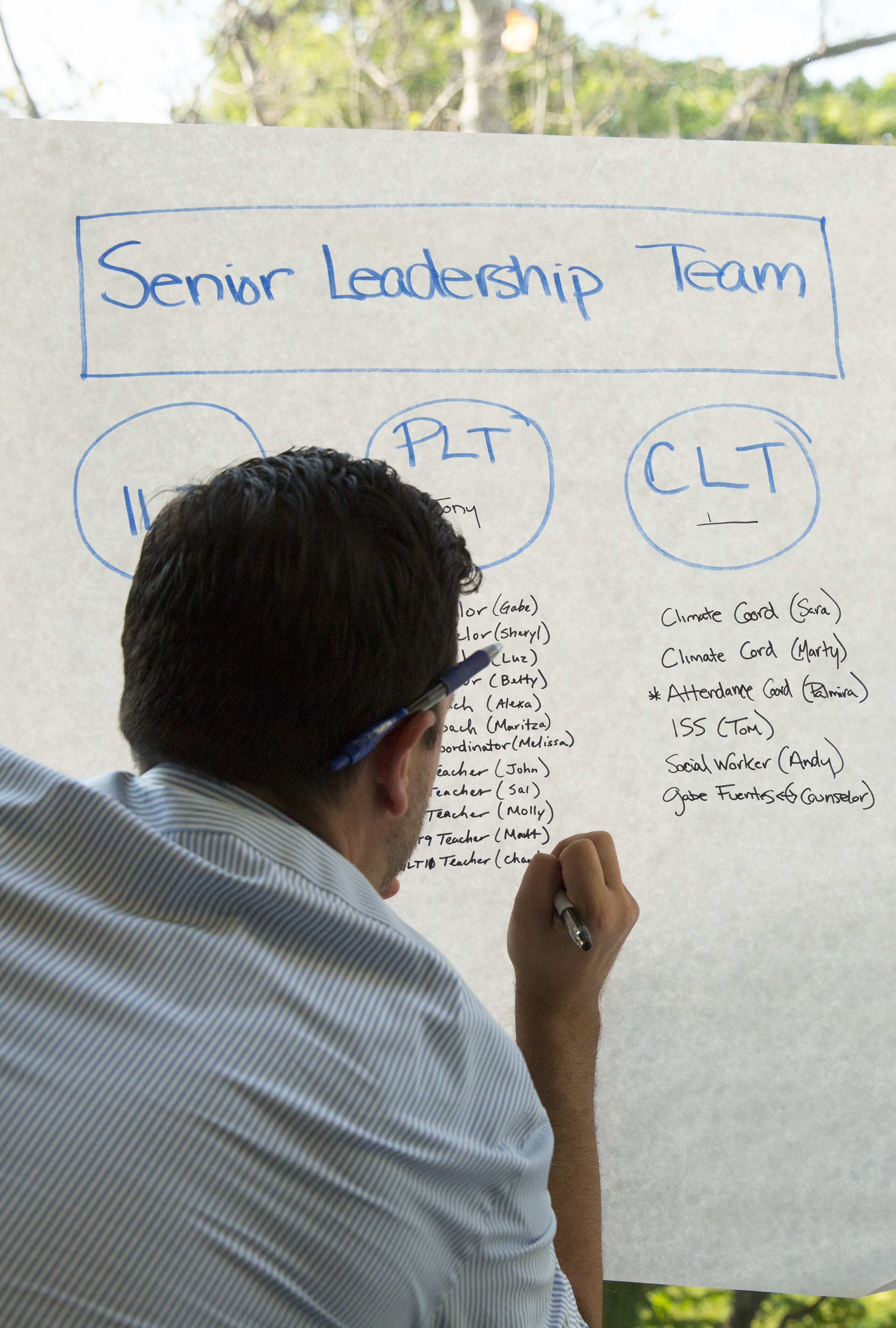

NCS also helps its schools create teams of leaders dedicated to overseeing instruction, counseling, literacy and postsecondary placement. A major focus for these leadership teams, and for NCS, is making sure that freshmen pass their classes. Again, NCS points to the research: Freshmen who pass enough classes to become sophomores are almost four times more likely to ultimately graduate than students who fail multiple classes their first year, noted Ms. Pitcher. Just getting by isn’t enough, however: “We know from research that high school grade point averages are the best predictor of kids’ ability to graduate from college,” she said.

So NCS gets its schools to identify the students who aren’t doing well and to figure out why — and then to devise interventions that can be quickly implemented and assessed. Which first-year students are falling behind in class? Might they benefit from lunchtime tutorials that help them catch up to their grade level? Are their grades suffering because an ineffective disciplinary policy doles out two-week suspensions that make it extremely difficult for suspended kids to recover? If so, could a new policy involve disciplinary action that doesn’t kick students out for minor infractions? And if students only sit in rows facing one another’s backs, could placing them in small discussion groups facilitate their interactions and their learning?

“In schools, educators are largely alone with those types of questions,” said Ms. Duncan. NCS ensures they’re not.

Among the total CPS high school population, 73 percent of students graduate within five years and 59 percent enroll in college. For CPS high schools that have partnered with NCS for over three years, those two figures climb, respectively, to 78 and 69 percent.

NCS schools aren’t the only ones to reap the benefits. The organization shares its best practices with all CPS high schools—which now have adopted, for example, the NCS practice of establishing a team of school leaders to oversee instruction. “Our schools serve as a research and development network where we test out innovations and then disseminate those practices to the rest of the district’s high schools,” said Ms. Pitcher